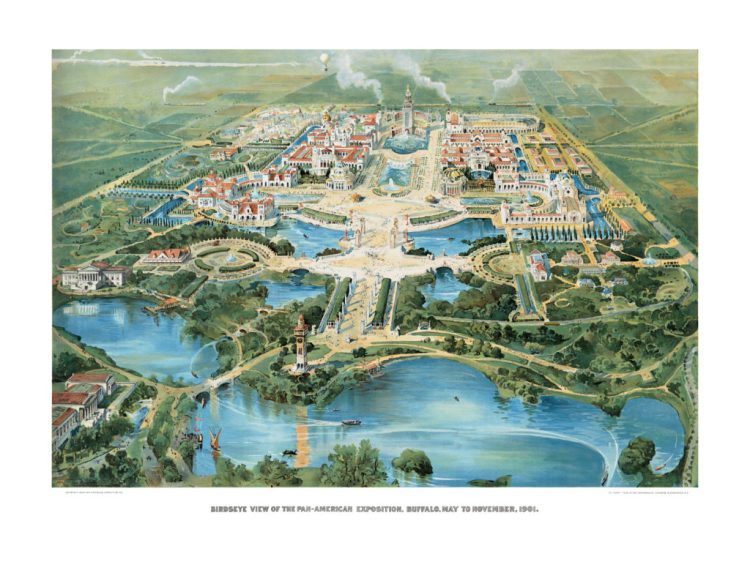

The eyes of the world were on Buffalo as it hosted the Pan-American Exposition in the summer of 1901. The Pan-Am was a world’s fair held between May and November. Its goal was to celebrate the achievements of the western hemisphere and foster better relations between the nations of north, south, and central America. It celebrated industrial, cultural, and technological progress-the centerpiece of which being the large-scale use of electricity to illuminate its buildings each night.

Over 350 acres of land between Elmwood and Delaware Avenues had been transformed into a resplendent complex of ornate buildings, pavilions, exhibits, and attractions. The fair was a glorious spectacle by day and, by night, it’s quarter-million light bulbs brilliantly lit the landscape. Over its sixth month run, an estimated eight million guests traveled from all over to visit the Pan-Am, for many, it was their first time seeing the spectacle of electricity.

William McKinley had planned to attend the opening of the Exposition in May as part of a longer nationwide tour. But his wife Ida, who was a fairly frail woman, became sick while on the trip. It was feared she was dying so the tour was cut short and they returned to Washington. McKinley sent his Vice President, former Governor of New York and the hero of the Spanish-American War, Theodore Roosevelt in his place. Given the magnitude of the fair, and the fact that he generally enjoyed expositions to begin with, McKinley rescheduled a visit for the fall.

On September 4th, 1901, the President’s train was met in Dunkirk by a welcoming party of local dignitaries including John Milburn – President of the Pan- American Exposition Company, John Scatcherd – chairmen of the Executive Committee, who boarded the train and accompanied the President the rest of the way to Buffalo.

The city was decked out in its finest to welcome the President. American flags and patriotic bunting could be seen all across the city and church bells rang out in a presidential welcome.

While often overlooked by history, it is important to mention that in 1901, McKinely was an enormously popular president. As an Ohio congressman, McKinley became one of the most vocal advocates of the protective tariff and while serving as the Governor of Ohio, he earned a reputation for balancing the interests of both business and labor.

In 1896, he was elected president, and, in his first term, the nation saw rapid economic growth. After guiding the U.S. to victory in the Spanish-American War in 1898, McKinley’s popularity soared. And, with the war’s hero Theodore Roosevelt as his running mate, he easily won reelection in 1900.

After arriving in Buffalo, McKinley and his entourage–comprised of his wife Ida, his nieces, his personal physician, private secretary, stenographers, two messengers, a maid, and a nurse, were taken to the Milburn residence on Delaware Avenue where they would be staying.

The following day, September 5th was celebrated as President’s Day at the Exposition. Over 116,000 people attended the fair—making it the busiest day by more than 10,000 visitors. McKinley began the day by addressing the crowd on the fair’s Triumphal Bridge. He spoke about tariffs, commercial expansion, the purposes of the Spanish/American War, and of course, Expositions—which he famously called “the timekeepers of progress.”

He attended several engagements throughout the day, including lunch at the New York State Pavilion, which is now the home of The Buffalo History Museum.

Early on the morning of the 6th, McKinley traveled to Niagara Falls to take in the scenery and view the power station providing the electricity for the fair. The guest book register from the station, which is now at the history museum, bears what is quite possibly the last signature the president ever penned.

By 3:30 McKinley was back at the Pan-Am rail station for his next engagement and thousands of people were already standing in line outside the Temple of Music hoping they might have the chance to shake hands with him. Some accounts report that McKinley could shake hands at a furious pace—as many as 50 hands per minute—and that he prided himself on this ability. I’d take this with a grain of salt, however.

Interestingly, this public event was removed from McKinley’s itinerary twice due to concerns about the President’s safety. Let’s keep in mind that in 1901, two presidents had been assassinated in the previous thirty-six years, AND King Umberto of Italy had also been killed in 1900. That being said, McKinley insisted that the receiving line take place. He, in fact, told his personal secretary George Cortelyou “No one would wish to hurt me.”

Cortelyou and McKinley came to a compromise. The reception WOULD happen, BUT, it would be EXACTLY ten minutes long and that additional security would be present….As fate would have it, that extra security might have actually compromised the secret services’ ability to scan the crowd.

In line was a 28-year-old man named Leon Czolgosz, though while staying in Buffalo, he used the alias, Fred Niemann translating to Fred Nobody in German. Originally from Michigan, Czolgosz was a laborer who also spent time working in Cleveland and who aligned himself with anarchist principles.

A few people ahead of Czolgosz was a young girl named Myrtle Ledger who liked the carnation McKinley wore on his lapel for good luck which, as a kind gesture, he gave to her.

Interestingly, directly in front of Czolgosz was a man that caught the attention of all the guards. They thought he looked “shifty and suspicious” and many had their eyes on him. Behind him, Czolgosz had the gun concealed under a handkerchief. We know the Secret Service wasn’t strictly enforcing an ‘empty hands’ policy that day because a man with a bandaged hand had already been allowed through. Also, it was a hot day and lots of people were carrying them- so it was not quite as suspicious as it may sound to our ears.

Now, after the questionable character shook hands with the president, the guards breathed a sigh of relief. At that moment, the organist reportedly had played the highest note in Bach’s sonata in F and had paused to let the notes reverberate when two shots rang out.

Czolgosz had approached the president and fired two shots from his .32 caliber Iver Johnson revolver. The first shot ricocheted off of one of McKinley’s buttons, and the second shot went into his abdomen.

Behind Czolgosz was an African American man named James Parker, who was employed as a server at an exposition restaurant. After the second shot. Parker punched Czolgosz in the back of the neck and tackled him to the ground… at which point other guards and agents piled on and began to beat the shooter.

McKinley then magnanimously directed them to go easy on his attacker…and Czolgosz was dragged into a small room behind the stage. There, he was locked in with agents to both interrogate him as well as keep him from the angry mob forming outside.

The President needed immediate medical attention and was taken to the hospital on the Pan-Am grounds. Like all the buildings at the exposition, the hospital was a temporary structure, ill-equipped and able to handle only the most routine medical emergencies. It was, effectively, a glorified first aid station.

Ironically, in a World’s Fair celebrating the new technology of electricity, there were no electric lights in its hospital. In fact, one of the attending physicians was forced to use a mirror to redirect sunlight toward where they were operating on McKinley. Only toward the end of the operation did they actually succeed in rigging up an electric light.

The doctor selected to do the surgery was Dr. Matthew Mann. Mann was an extremely accomplished local physician who served as “Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Buffalo. He had previously served as president of the American Gynecological Society and as a president of the Buffalo Academy of Medicine. And while Dr. Mann was a well established, talented, and able doctor…he was a gynecologist.

Now, one of the nation’s best trauma surgeons was Buffalo’s own Dr. Roswell Park. Dr. Park had traveled through Europe, studying the most modern medical practices. Upon his return to the US, he educated others on these practices—most notably, the importance of sterilization during surgery.

At the time of the shooting, Park was already performing surgery on a man in Niagara Falls. The legend– as told by Dr. Park’s son–was that during the operation, a man burst into the room and told Dr. Park that he was needed in Buffalo. Park then looked up from the patient and said, “Can’t you see that I’m not able to come, even if it were for the President, himself?!?”

Park WAS eventually was brought back to Buffalo on a special train, but by the time he arrived, the surgery was mostly complete.

Czolgosz’s bullet had punctured McKinley’s stomach and, despite the doctors’ best efforts, it couldn’t be located or removed… Ironically, one of the other technological innovations on display at the fair was the x-ray machine. However, as none of the doctors had any experience with it. Dr. Mann claimed that the machine would have been little use to the President and may have disturbed him.

McKinley survived the surgery and was taken by electric ambulance to the Milburn residence to recuperate. The doctors’ considered his condition to be critical and he was monitored around the clock. As his status was already so uncertain, it was universally agreed that any attempt to transport the president back to D.C. would be disastrous and that instead, he should remain in Buffalo.

Minutes after the shooting word spread to Washington through the Associated Press that the president had been shot, but official word wasn’t issued until three hours after the shooting. Vice President Roosevelt, who was in Vermont attending the Vermont Fish and Game League Banquet, first received word about the shooting at 5:30pm– almost an hour and a half after it happened– but the report was unconfirmed and its information, incomplete.

Once the information WAS confirmed and given the serious nature of the president’s injuries, Roosevelt hurried to Buffalo where he was met by his friend and local lawyer, Ansley Wilcox, with whom he had previously worked to create the Niagara Reservation in 1885. Wilcox offered his home to Roosevelt and, from September 7th to 10th, the Vice President made the residence his headquarters while in Buffalo. A telegraph machine was installed in the Wilcox house for Roosevelt’s use and the location became a hub of activity.

Like Roosevelt, members of McKinley’s cabinet slowly began to receive information about the shooting and subsequent operation. Over the following days, the cabinet, members of congress, governors, and other officials made their way to Buffalo to be at the president’s bedside.

The local newspapers referred to Buffalo as the “seat of government” with many of the Delaware Avenue buildings playing host to the prominent figures. The Buffalo Club in particular became the regular meeting place for the cabinet with at least two cabinet members, John Hay and Philander Knox staying there as guests. Senator Mark Hanna, a close friend of McKinley, requested updates on the president’s condition be delivered to the club in 15 minute intervals. This allowed the cabinet to be amongst the first to know his condition while respecting the doctors’ requests for peace and quiet at McKinley’s bedside.

In the subsequent days, Roosevelt made regular visits to the Milburn residence, where McKinley seemed to be recovering. Along with the President’s Cabinet, Roosevelt monitored McKinley’s progress carefully. Initial reports were positive and suggested that the danger had passed.

Despite the initially positive prognosis, Roosevelt was extremely aware of the optics of the situation. Though the cabinet was meeting regularly only a few blocks from where he was staying, he refrained from attending these meetings. He was concerned it would give the appearance of attempting to take over in McKinley’s absence. Insead, he held informal lunches during which cabinet members would keep him apprised of the conversations occurring.

On September 10th, when President McKinley’s recovery seemed likely, it was agreed that Roosevelt should leave Buffalo to demonstrate confidence in McKinley’s recovery and help raise the nation’s spirits. He left to join his family on holiday in New York’s Adirondack Mountains, but left an itinerary and contact information with Wilcox should the President’s condition change.

Three days later, on September 13, McKinley’s condition DID change. Though his condition had seemed to be improving, gangrene was growing inside him and passing into his blood. His condition only worsened throughout the day, drifting in and out of consciousness. The first lady mourned at his bedside, as did Senator Hanna and others. At 2:15am, the President passed away. Witnesses recount that McKinley’s final words were of his favorite hymn, “Nearer, My God, to Thee.”