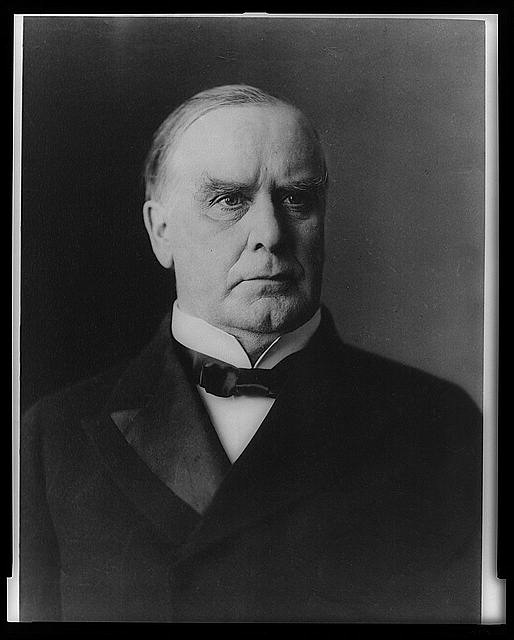

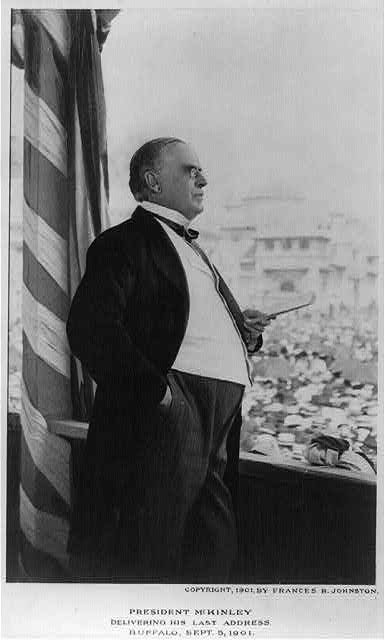

I did not set out to be a McKinley historian, however, as the City of Buffalo Municipal Historian, President William McKinley was unavoidable. His life and my city are inextricably linked as he was assassinated in Buffalo in 1901. That said, for most of my career, McKinley was not a president who often popped up in conversation. So, you can imagine my great surprise when recent events thrust the McKinley’s tariffs into the national spotlight.

Since I’ve been waiting my entire professional life for this moment, let’s talk about the McKinley Tariffs.

William McKinley and tariffs rightfully go hand in hand. As a Congressman, McKinley earned a reputation as the definitive authority on the subject, much like today how we immediately associate Senator Bernie Sanders with Democratic Socialism or the late Senator Ted Kennedy with healthcare.

At that time in American history, tariffs were a hot topic. The nineteenth century was a period of enormous change for the young American nation. The geographical footprint and the population inhabiting it increased exponentially. At the same time, industry and innovation grew dramatically. The United States began the nineteenth century as a small agrarian nation and was about to end that same century as an industrial and economic powerhouse poised to challenge European international dominance.

Tariffs were supposed to be a mechanism to protect these growing American industries. Europe, and especially England, enjoyed an international commercial advantage. England’s industrial might made the mass production of goods so inexpensive that even with the cost of shipping, many European-made goods were often less expensive than their American counterparts. Not only did this limit the sale of American-made goods, but it also discouraged the development and expansion of certain industries.

The American tin industry is the example most often associated with William McKinley. Prior to his tariff policies, Europe was so dominant in the export and sale of tin that few, if any, American companies attempted to compete. In 1890, McKinley’s legislation raised the tin tariff from 30% to 70%, which made tin exorbitantly expensive but incentivized the development of a new American industry.1

While this may sound good, even pro-American, McKinley learned firsthand the numerous downsides to tariffs. It turned out the American people did not like it when the cost of everyday goods increased dramatically, especially when it was for political reasons.

Protective tariffs are, by design, a tax on imported goods that makes them more expensive than similar domestic products. The entire tariff process occurs within the United States. Tariff rates are set by the United States government, they are charged at the time goods enter the country, and they are paid by the American companies importing the goods.

More often than not, the average American consumer is not the primary importer of the goods. Instead, companies bring in goods and then resell them to consumers. That means the company importing the goods pays the tariff to the American government. Tariffs raise the price of goods; that is their purpose. However, when companies have to pay more money to bring in the same products, that cost gets passed on to the consumer. So yes, technically, you are not paying a tariff to the American government. You are reimbursing a company for the money they paid to the American government.

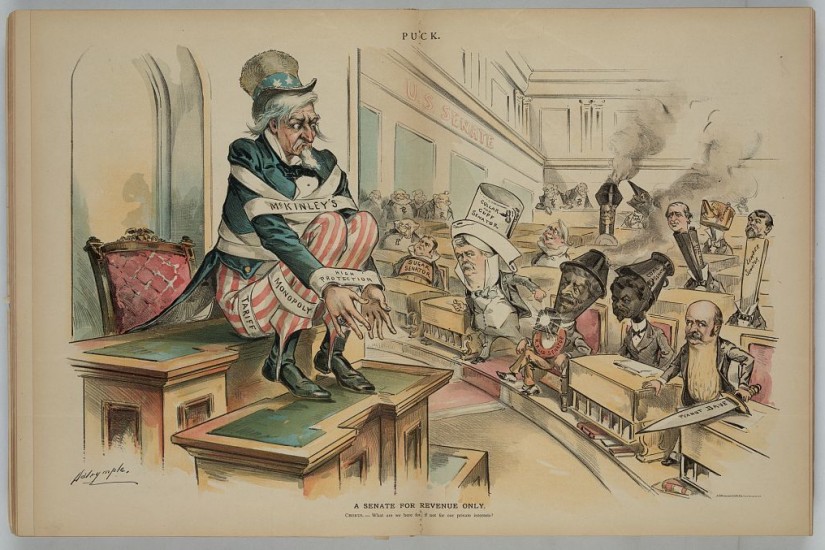

The Congressional Tariff Act of 1890 was the brainchild of then Congressman William McKinley, so much so, that it was quickly nicknamed the McKinley Tariffs. The act increased the cost of many common goods, including wool, metals like iron and steel, and even food products. Immediately, the cost of importing these goods increased, and that cost was passed on to consumers. People were paying significantly more for the same items.

These tariffs turned out to be so enormously unpopular that Republicans lost 93 congressional seats, including McKinley’s own seat, only a few months after the McKinley Tariffs passed.2 Even two years later, Democrats successfully campaigned on the failure of the Republican tariffs and easily won the 1892 presidential election. More disastrous for the American people, the economic conditions created by McKinley’s tariffs was a contributing factor to the Panic of 1893, an economic depression so terrible that it was known as the Great Depression until it was superseded by the stock market crash of 1929.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

What do the outcomes of the 1890 and 1892 elections reveal that current policymakers seem to be ignoring today? Simply put, while they sound good on the surface, tariffs hurt the American people. Tariffs are designed to increase costs in an effort to allow American industries to grow to meet market demand. But if history taught us anything, that action did not improve the lives of average Americans in the immediate aftermath. Salaries for workers remained low, consumer buying power decreased, business owners amassed enormous personal fortunes, and foreign nations retaliated with tariff policies that hurt American exports.

Further, even though American companies produced more of the market supply, the growth they may have enjoyed was offset by a lack of overall economic activity. As the price of goods went up, people simply bought fewer things. Few, if any, new jobs were created, and the average income for most Americans stayed stagnant while prices continued to increase.

McKinley managed to salvage his political career by running for the relatively powerless governorship of Ohio. There, he laid low long enough for the dust to settle from his disastrous tariff policy to launch a successful presidential bid in 1896. Though he continued to defend the need for protective tariffs, as president, he never advocated for new tariff legislation, and by his second term, his position actually evolved to favor reciprocal trade agreements. McKinley learned a valuable lesson from the 1890 Tariff Act, and so should we: higher tariffs hurt hard-working Americans.

- Robert W. Merry, President McKinley: Architect of the American Century (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, 2018), 70-83. ↩︎

- https://history.house.gov/Institution/Majority-Changes/Majority-Changes/ ↩︎